Roupell Park – 1820

Roupell family where developers who made a big mark on the area. In the years leading up to 1820 they purchased large tracts of land in the northern part of Streatham, land previously belonging to Lord Thurlow’s estate of Leigham Court. Beginning in the 1840s the family planned and developed Roupell Park, a prestigious, if not an ambitious, development centred on Christchurch and Palace Roads in Tulse Hil and Streatham Hill. The estate, aimed to attract the affluent, contained some of the largest properties yet to be seen in The. Development was spasmodic, with the estate not being completed until the late 1880s when building took place towards Tulse Hill.

The spiritual needs of the new residents were met by Christ Church, which was built in 1840–2 by James Wild, with interior decoration by Owen Jones. This grade I-listed church now finds itself located on a stretch of the South Circular Road.

With the building of Roupell Park, the area had almost developed its own identity. Concentrations of commercial and residential property could be seen flanking the high road and filling in the immediate area. Along the edge of the parish, marked by New Park Road, lay Thomas Cubitt’s Clapham Park development, and with continuing developments along Brixton Hill and Upper Tulse Hill, a suburban townscape had gradually unfolded.

We also discover the interesting history of the Roupell Park Estate, where the large Victorian houses, which once lined Christchurch and Palace Roads, provided large, comfortable homes for the popular author, Dennis Wheatley, the well-known comedy actress June Whitfield, and the famous comic postcard artist, Donald McGill

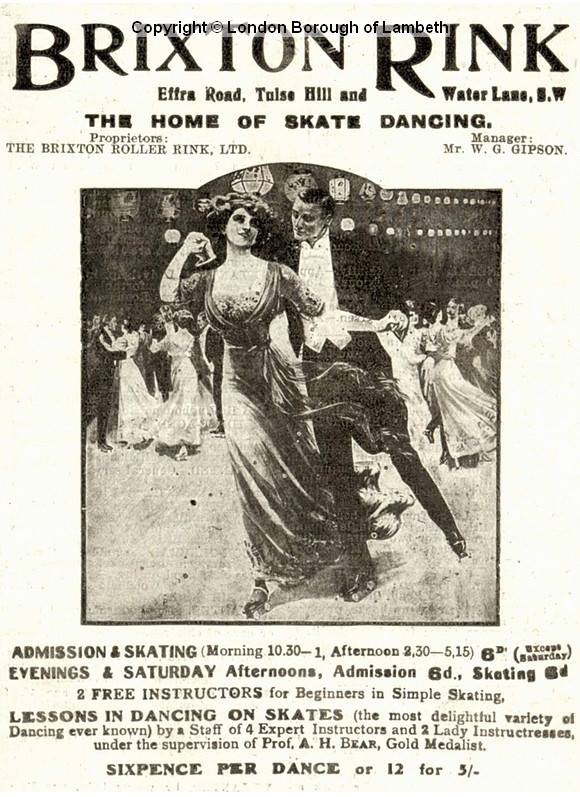

Roller Skating Rink Tulse Hill – 1914

A Skating rink was on the cross road of Tulse Hill, Brixton Water Lane and Effra Road. It opened around 1910 and was a popular entertainment venue until closure in the mid sixties. It became a carpet shop then a supermarket.

Tulse Hill Station Ghost – 1930

The unexplained sounds of heavy footsteps are sometimes heard by staff working at Tulse Hill station, south-east London. Most often at night the footsteps ascend the stairs to platform 1, pass through the barrier gates and proceed along the platform.

An unfortunate platelayer was killed here shortly after the introduction of electric trains and it is thought to be his ghost who still walks. On the night of his death he made his way up the very same stairs, walked through the same barrier and cheerfully greeted the duty porter. It was a cold and windy night when he made his way along the track and, knowing a train was due along the down line, he opted to step onto the up line track instead of the trackside cess.

He was run down and killed when the approaching steam-hauled train drowned out the sound of a late running and less noisy electric train.

Friends Meeting House, Streatham and Brixton – 1950

This building is found on the South end of Roupell Park Estate. It is a plain building of the late 1950s, designed by the well-known Quaker

architect Hubert Lidbetter, located within this post-war housing estate.

The meeting house was built in 1957. The meeting house was built after the Second World War in an area thenundergoing major rebuilding. It is an unusual example of a purpose-built Quaker meeting house incorporated in a post-war housing estate; The building is a modest design by Hubert Lidbetter, a Quaker architect of

note. It has a pleasing domestic character and is relatively little altered,retaining its original Crittall windows and doors, and pantile roof. It is of medium aesthetic value.

The building is valued by the meeting and other users, for its facilities and its tranquil garden setting. It could probably be put to greater use. As it is, it is of medium communal value.

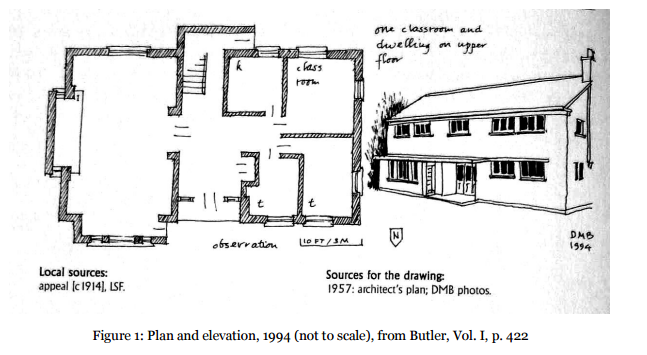

In about 1915 a house on Brixton Hill was acquired and adapted to serve the needs of the local meeting. This was compulsorily purchased and demolished by the local authority in 1953. Thereafter the meeting used a local Methodist Hall until 1957, when the present building, designed by Hubert Lidbetter (of H. and H. M. Lidbetter, of 2 Verulam Buildings, Grays Inn, WC1, and Surveyor to Six Weeks Meeting) was opened. Built on the edge of the then newly-developed Roupell Park Estate, this had the main meeting accommodation on the ground floor and a classroom and three bedroom flat for the warden above. The ground floor plan and elevation as existing in 1994 are shown at figure 1.

A clock tower/cupola shown on the ridge in the original designs (copies of which are held at the meeting house) was omitted from the final design, presumably on grounds of cost.

The building and its principal fittings and fixtures The meeting house was built in 1957 from designs by Hubert Lidbetter. It is of domestic

character, of two storeys, built of straw-coloured Fletton-type brick laid in Flemish bond with pantile roofs. An originally flat-roofed porch and side projection for the meeting room have been renewed with pitched pantile roofs. The meeting house retains its original metalframed Crittall windows and doors, apart from a pair of French doors adapted from a window on the rear elevation (giving off the main meeting room), which are in white powder coated aluminium. Sills are of creased tiles, window arches have soldier courses. At the rear is a staircase projection with brick on edge patterning below the landing window. A stack is placed on the west gable, corbelled out from the first floor flank elevation. From the entrance hall, the meeting room gives off to the left, and a smaller meeting room, kitchens, and WCs to the right. A concrete staircase leads up to the first floor, where there is a classroom (now office) and a warden’s flat (now let and not inspected). The floor construction throughout is of concrete. The ground floor has parquet floor finishes. In the main meeting room, a raised elders’ platform is placed in a recess on the west side. On the east side, some original cupboards and bookshelves remain in situ.

Loose furnishings

There are none of particular note, apart from one open-backed bench on the elders’ platform

in the main meeting room, of unknown date and provenance.

Attached burial ground (if any)

Not applicable.

2.5. The meeting house in its wider setting

The meeting house is located towards the top of Brixton Hill, set back from the road and somewhat hidden away on the edge of the post-war Roupell Park estate. This is a large development of mid-rise post-war social housing, not unattractively laid out, with areas of grass and mature tree planting, but with a high level of deprivation. The estate and the meeting house border onto, but are not included in, the London Borough of Lambeth’s Rush Common and Brixton Hill Conservation Area. The meeting house is placed within a large and well-maintained garden, beyond which are the backs of the houses in the attractive latenineteenth-century terraced development of Holmewood Road and Gardens (which are in the conservation area).

Listed status

The meeting house is not listed and is not considered to be a candidate for listing. Although architecturally modest, it was designed by a Quaker architect of note and is of some local historical interest. It may merit inclusion in the London Borough of Lambeth’s local list, or it could (with a minor adjustment to the boundary) be brought within the Rush Common and Brixton Hill Conservation Area.

Archaeological potential of the site

Probably low. Until the 1950s, Brixton Hill consisted largely of early nineteenth century and Victorian villas, set back from the road, with large gardens and (well into the nineteenth century) fields and orchards behind. The early history of the site of the meeting house has not been researched, but it does not appear to have been previously developed, and in any case any below-ground archaeological remains would probably have been damaged if not lost at the time of construction; the meeting house has very deep piles at one end, which might suggest poor soil conditions, or possibly the site of a wartime bomb crater (see

http://bombsight.org/bombs/17463/).

Cressingham Gardens – 1950

History

The 1969 Lambeth Council was controlled by the Conservative Party. The Conservatives, at that time, believed that the council should provide homes for all those who could not afford to buy a house. In inner London, in the 1950s and 1960s, estates with multi-storey apartment blocks provided the dominant architectural model for council housing. The seminal study Family and Kinship in East London showed that such apartments did not prove as satisfactory a family home as a house with a garden. By the 1970s many councils were returning to building houses, rather than multi-storey apartment blocks, and Lambeth Council was a leader in this trend.

As Borough Architect, Ted Hollamby had designed different types of council dwellings, tower blocks, tenements, houses. He ‘passionately believed that council housing should be as good, if not better than private housing’.[4] His design for Cressingham Gardens was informed by failure of multi-storey tower blocks to provide good family homes.[5] He was also aware of the importance of gardens in enhancing the quality of life of the residents of a dwelling, His design for Cressingham Gardens ensured ‘every home its splash of greenery and colour’.[6] In recognizing the importance of gardens, he was following an English tradition of the garden city and garden suburbs.

The variety of dwelling types allows careful control of the height of the development such that is does not project above the tree line when viewed from Brockwell Park.

The estate is built in a U shape around a central green open space, the highest buildings being nearest Tulse Hill and on the outer edges, and the lower ones at the centre.

“Thus, as many people as possible will get fine views from their new homes” quoted the Lambeth News Release.

The thoughtfulness of the design and how it fitted with the local topography and landscape is best described in the original design brochure:

It is proposed to provide all the accommodation needed in low rise dwellings. This wil avoid any visual obtrusion on the views from Brockwell Park and will ensure that all dwellings will have a close contact with the site.

Part of the plateau has been kept clear of buildings to extend the landscape of the Park into the site. The buildings are arranged around this in such a way that the lower buildings are adjacent to it with the height increasing to a maximum of four storeys around the perimeter of the site away from the park.

Among these buildings as many of the existing trees as possible will be retained and where necessary will be reinforced by new planting. Along the Tulse Hill frontage virtually all the trees adjacent to the boundary will be retained.

Vehicles generally are kept to the perimeter of the site, one short service road being provided to serve the Northern part of the site including the nursery school. A longer one having access onto both Tulse Hill and Trinity Rise serves the remainder of the scheme.

Garaging is provided under the higher blocks around the site perimeter adjacent to the service roads. Within the site access to the dwellings is entirely pedestrian although provision will be made for fire brigade vehicles, ambulances etc to get close to all dwellings in emergencies.

In 1969 Ted Hollamby submitted his team’s design for Cressingham Gardens to the Housing Committee. The deputy chairman of the housing committee was Sir John Major. The committee recognized the exceptional importance of the innovative design and minuted ‘congratulations to Cressingham’s architects on their ‘bold and imaginative scheme’.[7]

The initial contract for the building estate was for £1.58 million, or approximately £5,500 per dwelling.[6] If the retail price index is used to convert to 2015 prices the costs are: £24 million for the build, with a cost per dwelling of £80,000.[8]

The building of Cressingham Gardens was interrupted by a national building strike, and the contractors terminated the contract. In 1970 Lambeth Council became Labour controlled. To complete the estate, the new housing committee, on the advice of Ken Livingstone, who was deputy chairman, authorized the use direct labour. Building the three hundred dwellings took seven years.[6]

Timeline

January 1963 – Ted Hollamby became Lambeth’s first borough architect (title “Borough Architect and Town Planning Officer”). Started work with two qualified and twenty unqualified assistants.

November 1963 – First Compulsory Purchase Orders made by Lambeth for the Tulse Hill site

September 1966 – Minister of Housing and Local Government confirmed CPO for the acquisition of the area of land to form the nucleus of the Tulse Hill Redevelopment Scheme

March 1967 – Design of estate started – based on records at Ove Arup structural engineers

October 1967 – Council approval for the provision of a nursery school as part of the Tulse Hill Redevelopment scheme

January 1969 – Development brochure presented and scheme approved by Housing Committee (20th Jan 1969) and Full Council (12th Feb 1969)

February 1971 – Carlton Contractors chosen for construction of the estate after tender process

September 1971 – CPO made by Council for 107 Tulse Hill (northern end of the estate)

May 1971 – Work started on site with a forecast completion of January 1974

June 1972 – Contract reported to be 25 weeks behind schedule

October 1972 – Further delayed by the National Building strike which stopped work on site

February 1973 – Site of 107 Tulse Hill and land at rear acquired by Council (northern end of estate)

June 1973 – Carlton Contractors withdrew all labour from the site. Lambeth’s Directorate of Construction Services took possession

February 1974 – Council approved Phase 2 (northern end of estate 23 units). “In all cases the dwellings are the same as those now under construction on Phase I using the same plane, elevational, and sectional form.

June 1974 – Lambeth’s own Directorate of Construction Services takes over the construction of the estate

September 1974 – Appointment of Dry, Halasz Dixon Partnership to provide partial services on a time-basis for work stages E, F, G and H

April 1976 – Estate and accesses named

June 1977 – First blocks finished and handed over (Block nos 3 and 4)

November 1977 – Housing Committee approved the scheme for the Pre-School Playgroup (known as the “Rotunda” today). Dry Halasz Dixon Partnership (later renamed Dry Hastwell Butlin and Partners) appointed to complete the necessary presentation / working drawings for the building in order to enable a tender. Design work on the scheme had already been completed internally by Lambeth.

June 1978 – 172 units completed and handed over

September 1978 – Handover of final blocks on estate